Sustainable Forestry & Wood as Building Material

For our newest lab project (stay tuned!), we went to the “Klimapfad Berlin” to learn more about forests, trees, and sustainable forestry.

The Klimapfad is an outside exhibition along a 1,5-hour hike within the forest (Grunewald) initiated by the city of Berlin to make more people aware of the importance of forests. It's a learning experience for young and old and worth visiting. This is the starting point of the 1,5-hour hike.

Our friend, and happy pigeon, Julia, is an expert and passionate about forests. Currently working for the social initiative Nabu, we were happy and grateful to get a guided tour with much stimulating information.

Julia von der Nüll

“Julia is a true change agent, contributing to a more sustainable and climate-change-adapted world. She believes that communicating scientific findings to decision-makers and the community needs to empower people and create a better understanding of their opportunities. She has done empirical studies in the forest and in cities, always connected to the adaptation to climate change. Her main interest is to better understand nature and the world that we are living in and to share this knowledge and make it accessible to everyone.”

LinkedIn

This article is a recap & summary of our tour to give you guys an impression of our learnings this day. In addition, we added some related information about wood as a building material.

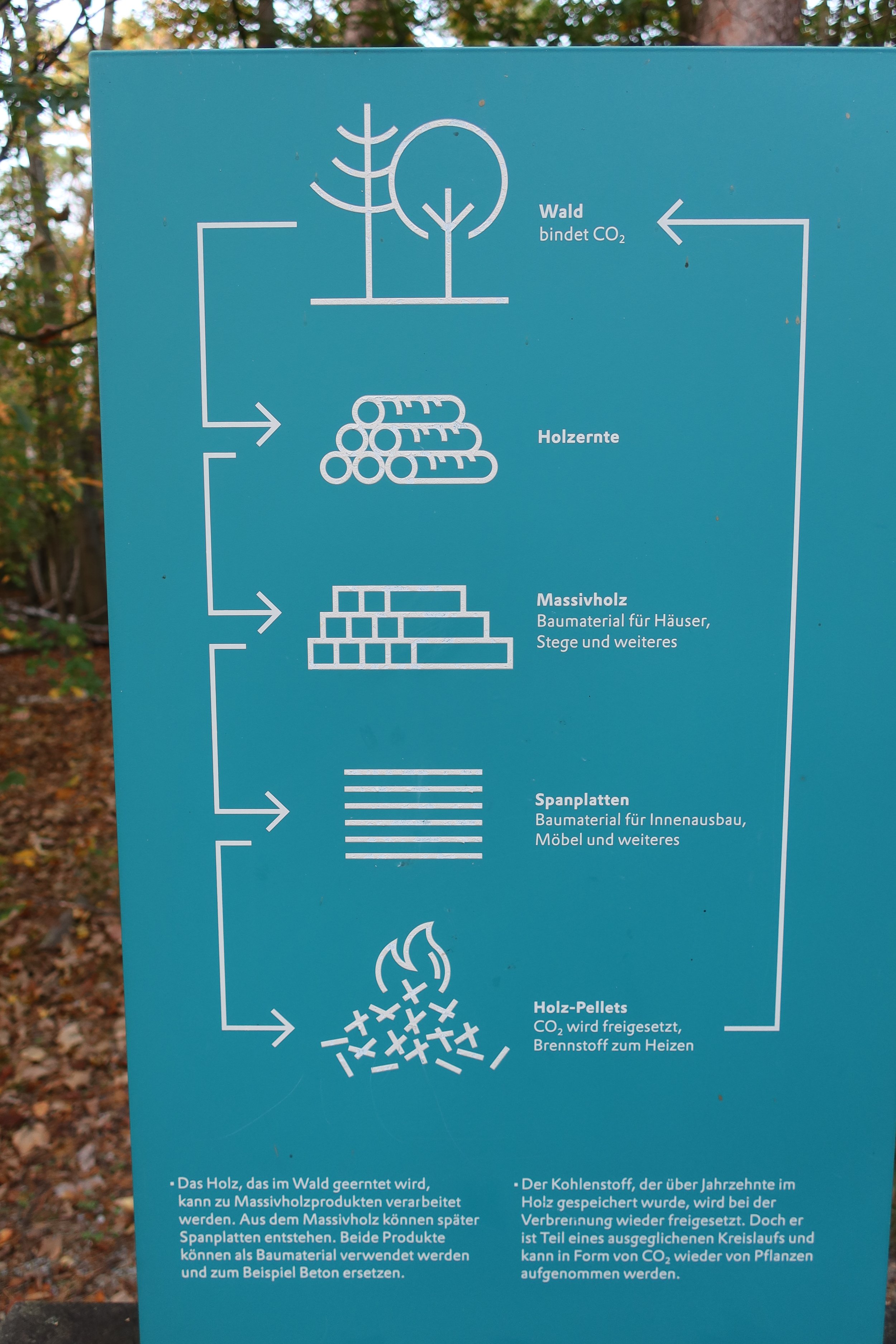

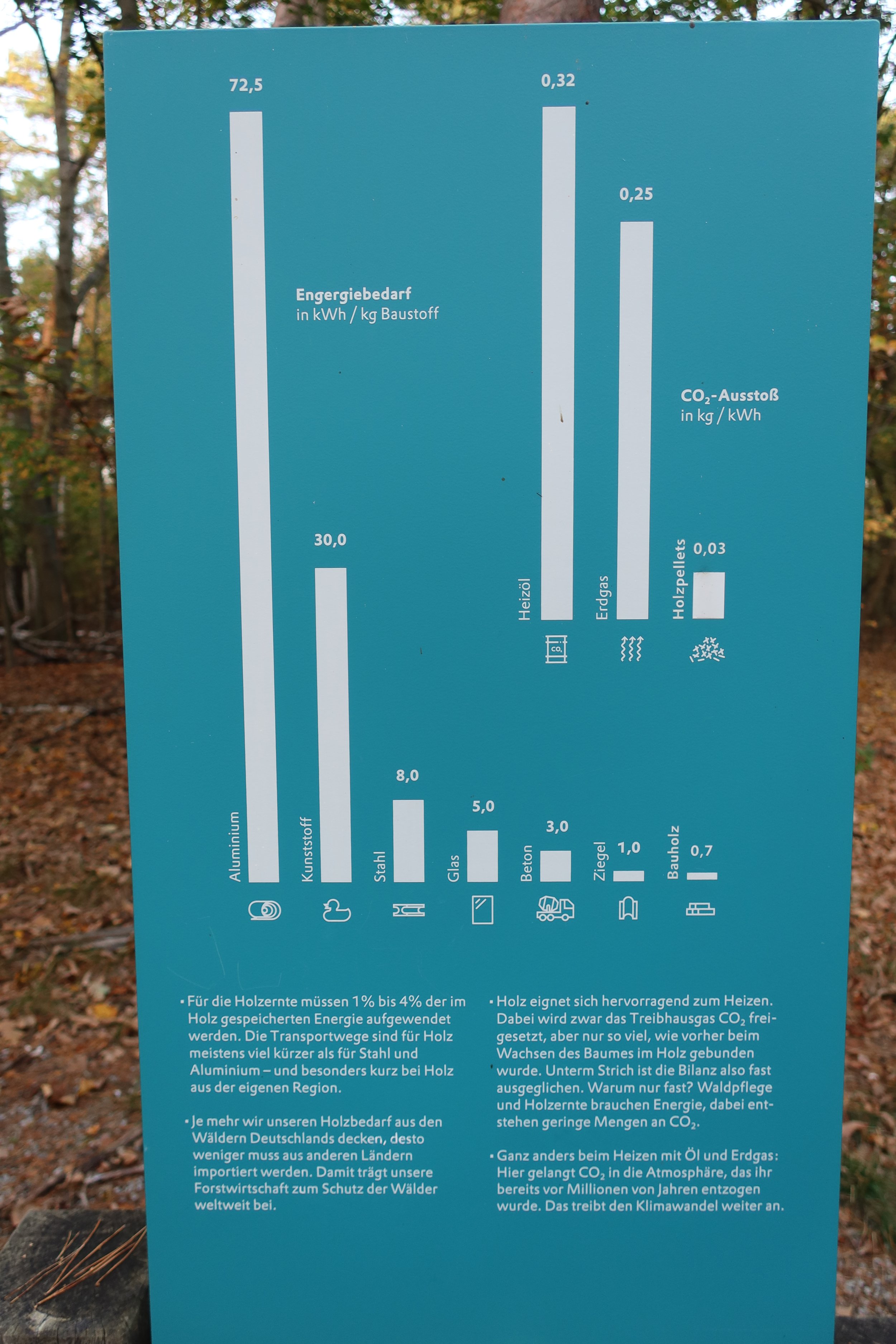

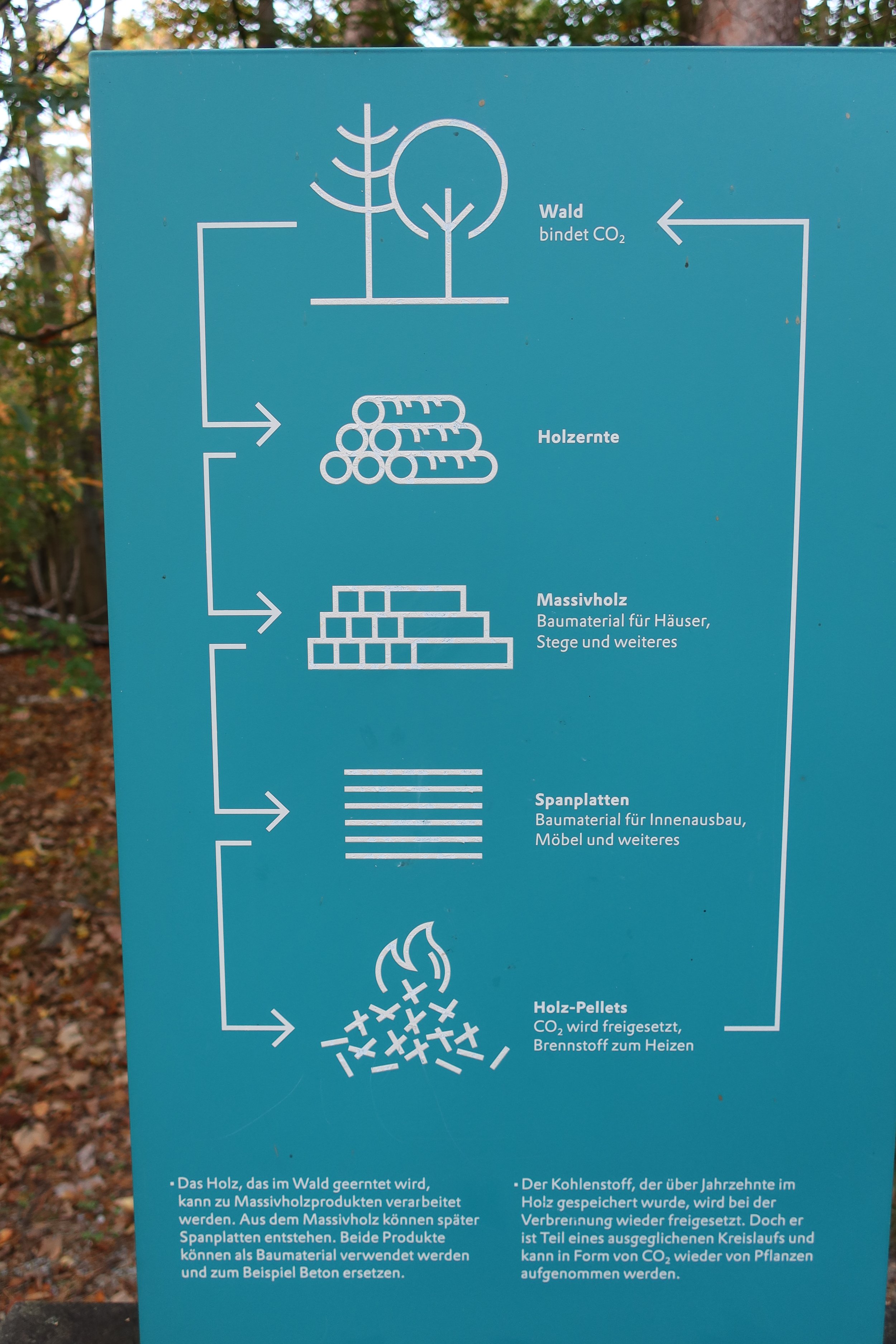

Julia started the tour by asking us, “How much of the (land mass) surface of the world is forest?” The answer is around 30 %, which is also the number in Germany. However, there are no more natural forests in Germany anymore. Julia explained: “After the war, Germany needed to compensate for its wrongdoings to its former enemies. Many of these compensation payments were made in the form of materials such as wood”. To pay as much and as fast as possible, many forests were updated to monocultures of conifers. The big advantage of spruce, pines, and larch is that they grow much faster than deciduous trees (such as oak) and can be cut and used as material sooner. Furthermore, there are also softer and lighter than deciduous wood, therefore easier to cut and transport. Unfortunately, these monocultures create many problems in the long run: the soil gets worse (fewer nutrients), and erosion is likely to happen. These conditions make it a nice habitat for harmful insects, which can spread over the whole monoculture area and drive away other helpful insects. Also, other animals might migrate to other, more nutritious areas. All in all, monocultures mean no good for flora and fauna in general. The natural ecosystem is slowly weakening over time. “This is why Germany has been actively taking measures for some time now to return to mixed forests,” Julia explained.

Conifer-monoculture and the active measure to return to a mixed forest: Young deciduous trees growing on the bottom.

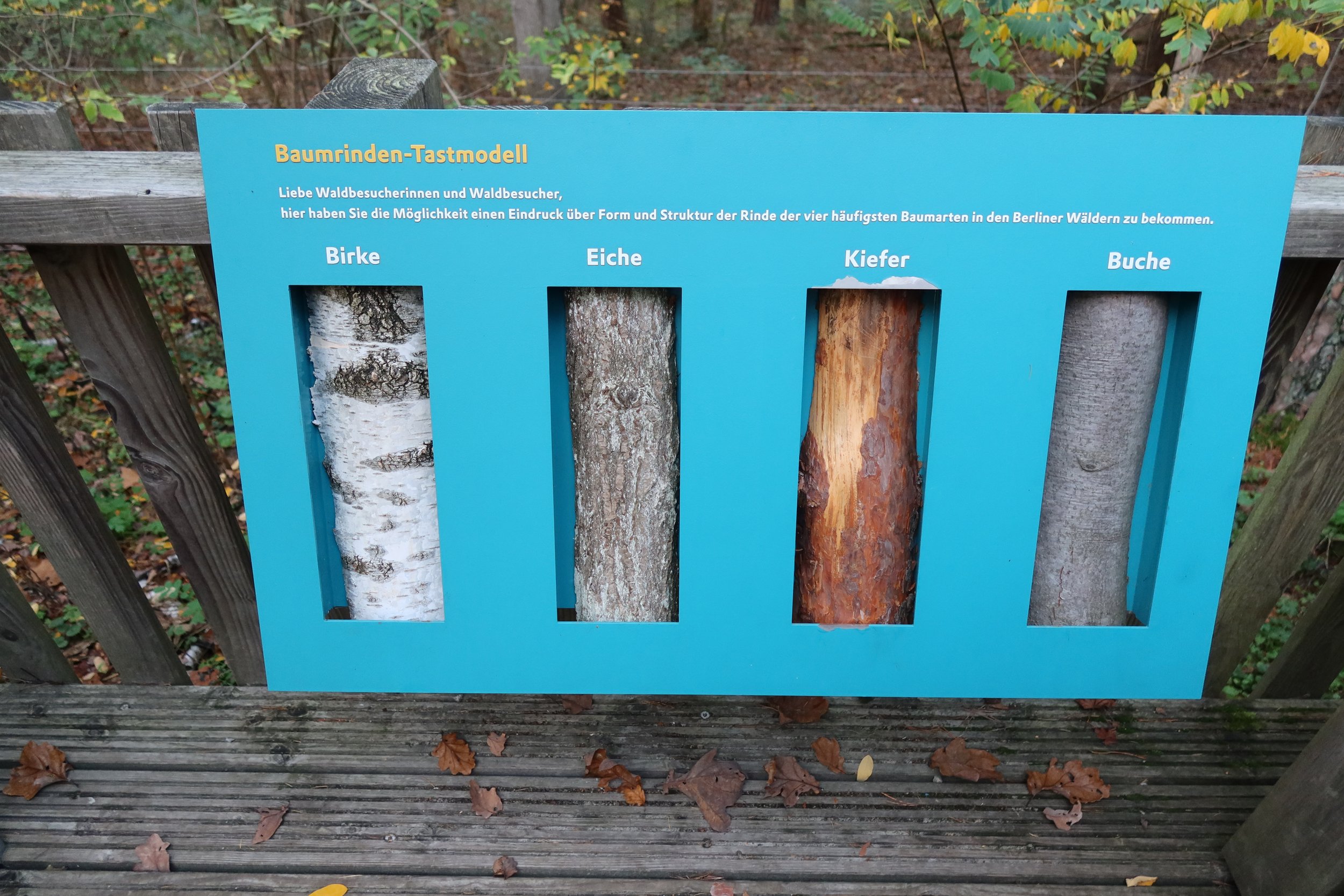

Characteristics of deciduous wood

Examples: Oak, beech, maple

Grow slower then conifer wood

Hard & heavy

Used in interior construction (e.g. floors) and for furniture

Harder to process than conifer

More durable and robust than conifer

Characteristics of conifer wood

Examples: spruce, pines, and larch (inter alia)

Grow fast

Soft & light in weight

Used as building material (timber), e.g. for houses, roofs etc

Easy & fast to process

Less durable due to softness

Despite of all measures, Berlins forests still consist of around 60% pine trees (monocultures). However, oak trees are on the rise consisting already around 20% of Berlin’s forests.

Art piece from the outside exhibition, showing what Berlin’s forest are consisting of: 60% pine, 21% oak, 10% other deciduous trees, around 5% other conifer trees, and 4% beech

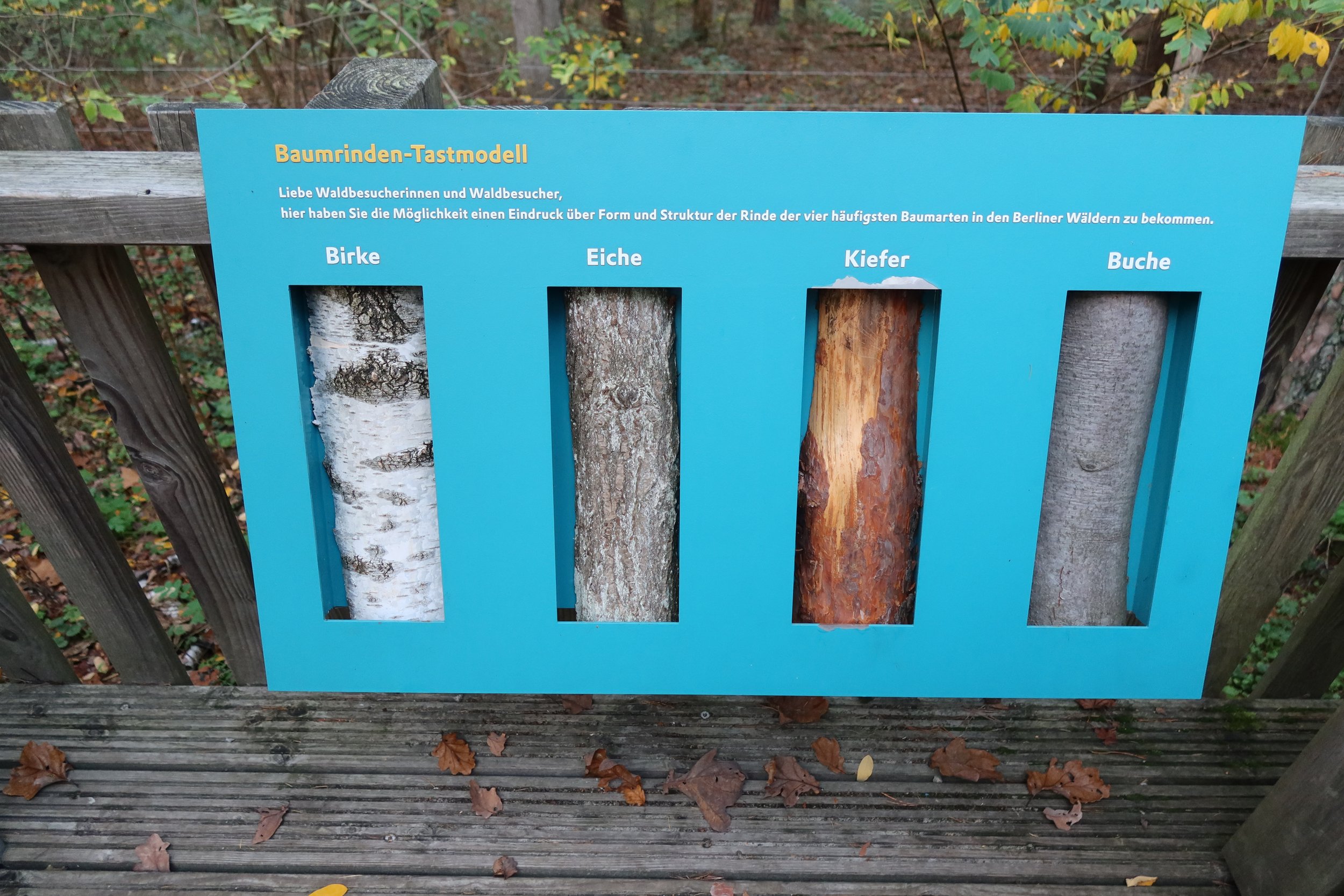

Mixed forests have the huge benefit of storing twice as much CO2 as monocultures. One of the reasons is lying in the soil: In contrast to conifers, deciduous trees drop their leaves once a year in autumn. In deciduous forests, therefore, more carbon is stored in the litter (falling leaves), dead wood, and soil.

Physical properties of wood concerning construction

Even though proportionally light in weight, it is pressure-resistant and load-bearing in terms of static

Heat regulating & insulating properties due to its open pores

Humidity regulating properties: it absorbs moisture when too humid and gives it back in hot/ dry conditions. It, therefore, creates a pleasant and healthy indoor climate.

Downside: hardly any step and sound insulation between rooms

But what does this all mean for us, the end-users, who want to use sustainable wood as a building material? How can we know if the wood we find in the construction market comes from sustainable forestry? The best way is to look for certificates, which the FSC certificate (Forest Stewardship Council) is the most well-known and accepted one. All forests in Berlin hold the FSC certificate.

However, as with many other certificates (from other industries), the FSC certificate has flaws. It has been criticized for giving certifications to monocultures, using the clearcutting practice (cutting all trees in our area), and being intransparent, among other things. Another challenge for the end user is that the retailers (construction market) are usually not part of the chain of custody (that is given the FSC certificate), as they do not process or repackage the wood products but only offer them for sale. Therefore, the retailers are only offered a so-called "N-License" (Non-Certificate Holder), which authorizes them to use the FSC trademark in advertising and public relations. Unfortunately, this makes it impossible for the end user to find out what kind of FSC certificate the particular wood product holds. Worst case, it does not hold any certificate (because the “N-License” is wrongly used).

All in all, it is still quite challenging for end-users to buy wood from sustainable forestry. It has to be made more accessible and transparent so that the end user can make a conscious choice for sustainable products.

Sources & further information

IKEA supplier Swedwood in Karelia: TV documentary exposes impacts of FSC certified clear-cuts in HCV forests. FSC Watch. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2022, from http://www.fsc-watch.org/archives/2011/11/10/IKEA_supplier_Swedwo

HUANG, Y. (2018). Impacts of species richness on productivity in a large-scale subtropical forest experiment. https://www.science.org/. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aat6405

Gerber, M. (2019). FSC - ein Siegel für das gute Gewissen? www.ardmediathek.de. https://www.ardmediathek.de/video/w-wie-wissen/fsc-ein-siegel-fuer-das-gute-gewissen/das-erste/Y3JpZDovL2Rhc2Vyc3RlLmRlL3cgd2llIHdpc3Nlbi8wMDZlN2NlOS1jOWIyLTQ4NmEtYmFmZi05ZTRmZmYxMTQ4Njg

Greenpeace Schweiz (2017). Waldschutz: Greenpeace Schweiz setzt auf Unabhängigkeit gegenüber FSC. https://www.greenpeace.ch/. https://www.greenpeace.ch/de/story/20260/waldschutz-greenpeace-schweiz-setzt-auf-unabhaengigkeit-gegenueber-fsc/

Liedl, P., & Rühm, B. (2019). Gesundes Bauen und Wohnen - Baubiologie für Bauherren und Architekten.